Following the Civil War, which devastated most of northern Virginia, the recently-formed Mount Vernon Ladies' Association (MVLA), protector of George Washington's historic home, relied on the sale of photographs to visitors. This created an important collection of nineteenth-century views of Washington's home at Mount Vernon.

Mount Vernon and the Civil War

Shortly after the outbreak of war in 1861, federal troops crossed the Potomac River and captured the town of Alexandria, Virginia. Union forces occupied the territory just north of Mount Vernon during the entire war. President Lincoln's Secretary of War prohibited civilian boat traffic on sections of the Potomac River. As a result, visitation to Washington's home practically ceased. This was devastating as entrance tickets were a major revenue stream.

Learn more about Mount Vernon during the Civil War

Sarah Tracy, the first secretary of the MVLA, cleverly found ways to overcome this difficult situation. She began by making small bracelets of coffee beans to sell to visitors. At the end of the war in 1865, Miss Tracy industriously set about making small bouquets of flowers and sold them to soldiers. That same year, Miss Tracy pressed the Regent, Ann Pamela Cunningham, to consider the sale of photographs of Mount Vernon to visitors. This suggestion helped to create an important collection of nineteenth-century views of Washington's home at Mount Vernon.

The first photographer to realize the profitability of taking photographic views of Mount Vernon was N.S. Bennett of Alexandria. In a letter to Ann Pamela Cunningham in October 1858, Susan Pellet stated Bennett's desire to sell photographs of Washington's home. At the time of Mr. Bennett's inquiry, he also was experiencing financial hardship. Therefore he proposed that he would collect all the money from the sale of photographs and pay Mount Vernon its rightful percentage later. Miss Cunningham evidently did not like this arrangement despite Mr. Bennett's gift to her of an ambrotype of the vault.

For several years following Mr. Bennett's offer, Ann Pamela Cunningham adamantly opposed any photographer at Mount Vernon and clearly distrusted photographers viewing their profession as "only a way to make money out of Mount Vernon." However, she was not willing to abandon photography altogether. She concluded in 1865 that the only way to allow the sale of photographs of Mount Vernon was to pay someone for this service. The parties involved would not be allowed to sell them nor to give copies to anyone but the MVLA.

Sarah Tracy was distressed over Ann Pamela Cunningham's suspicions. She knew that during the winter of 1865 the Vice-Regents "were talking about

how good a thing it would be if the Assn. could have views taken to be sold here." She quickly realized after the conclusion of the Civil War that the sale of photographs "is a source of income of which the Assn. should not be deprived." Consequently, she began in April to search for a photographer to dissuade the Regent of her fears.

Verifying Images

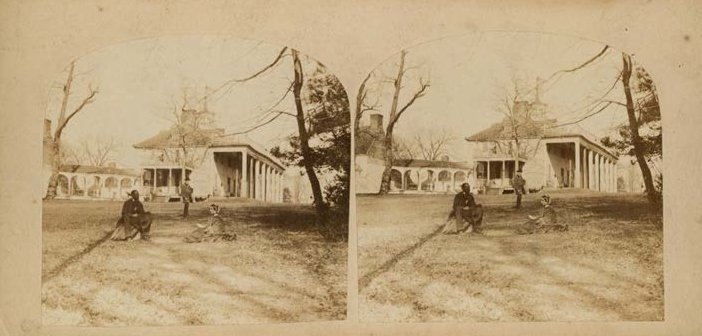

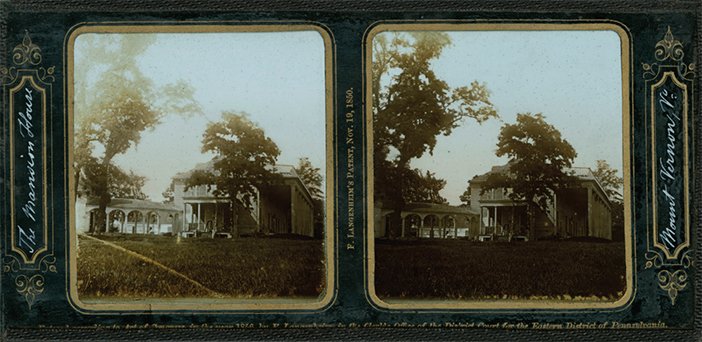

Nineteenth-century photography did not have the luxury of imbedded metadata. Dates printed on glass mounts did not always accurately reflect the date the image was taken. Our preservation staff took a look at the two stereoview images below and, using other Mount Vernon historical references, came up with a differing date to the Langenheim stereoview (Image 2) seen below. Click on various portions of both images and have a look for yourself.

The 1856 copyright date of Image 2 places this as one of the oldest views of Mount Vernon, but the content of the photos and the copyright date don’t quite fit, according to our preservation staff. Primary sources from the early days of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association ownership of the property, offer clues and insights for dating these images. Our preservation staff conclude that Image 2 was taken around 1860-1861.

According to Mount Vernon records, ship masts held up the piazza roof from 1850 until the piazza was rebuilt in 1860. Notice that the masts appear in Image 1, but are missing in Image 2.

There are clearly eight square pilasters (columns) on Image 2, but only seven appearing in Image 1. There is a ship’s mast in the spot of the missing pilaster (second from the left).

Image 1

Mansion, South East View (London Stereoscopic Co., Copyright 1859-1860)

Image 2

Mansion, South East View (Langenheim Bros., Frederick and William, Copyright 1856)

Here are some additional observations about Image 2 by our preservation team. See what other interesting items you can see!

- You can see what looks like a baby pram (or a large covered wagon, depending on the distance) either on the colonnade or just beyond it.

- There seems to be some serious rot issues on the southeast corner of the house. It looks like the siding has been removed between the corner and the door. You can even see the discoloration in the same spot in Image 1.

- It looks like they’re in the process of painting the south side of the Mansion (which is facing the camera). Could this explain the ladder on the portico?

- The Servants’ Hall (in the distance beyond the colonnade, the colonnade and the lower half of the kitchen (to the left in the image) look to have been already painted.

- It’s interesting to note that there is a railing only on one side of the colonnade.

Alexander Gardner

Alexander Gardner, the noted Civil War photographer, became the first of three "official" photographers at Mount Vernon.

During the early part of the Civil War, Alex Gardner worked as a photographer for Matthew Brady. Gardner is today well-known for his often controversial views of Civil War battles showing dead soldiers heaped on the battlefield. Differences between the two men (Brady took credit for Gardner's photographs) eventually forced Gardner to leave Brady's studio before the end of the War. He subsequently located his own studio in Washington, D.C.

Gardner signed a contract with the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association in late 1866 or early 1867 and compiled 45 stereograph titles featuring interior views of the mansion and exterior views of the estate. Gardner did not limit himself to stereographs, however, as he is known to have produced views in carte-de-visite and cabinet card format. Gardner enjoyed a relatively long tenure as Mount Vernon's official photographer until 1878.

N. G. Johnson

In 1878, N. G. Johnson, assumed his duties as the new photographer at Mount Vernon.

Like his predecessor, Alex Gardner, Johnson's photographs included stereoscopic and cabinet card views. When printing the former, Johnson included his name and the title, "Only Authorized Publisher of Mount Vernon Views." During the period of his contract with Mount Vernon, Johnson operated from several offices in Washington, D.C. Johnson photographed all aspects of Mount Vernon, including the interior of the Mansion, the outbuildings, and the two tombs. Often Johnson also printed a brief explanation of the photograph on the reverse side of the view. Johnson sold his views to Mount Vernon at $1.20 per dozen.

In the main, Johnson proved to be a satisfactory and dependable photographer for the MVLA. However, he aroused the consternation of the MVLA in 1882, as a consequence of selling unauthorized views of Mount Vernon in Washington, D.C. Then during the MVLA's Council Meeting in 1883, they decided not to renew Mr. Johnson's contract.

Luke Dillon

The MVLA voted to select Luke Dillon as the next "official" photographer in 1883. From the start, it was evident that his approach to taking photographs would be different from either Gardner or Johnson. An enthusiastic journalist writing for a local paper in 1884 about Mount Vernon commented that "a novel feature has been added to the attractions - visitors are photographed with the house itself." Whereas the previous two photographers attempted to document mostly the historical buildings of Mount Vernon through photography, Dillon sought equally the opportunity to immortalize its visitors.

Dillon soon realized that passengers traveling to Mount Vernon by boat could be enticed to have their picture taken while en route. Beginning in 1887, reports revealed that Dillon was "annoying" visitors on the boat and on the grounds. Complaints portray Dillon as having frequently solicited visitors as photographic subjects. He then sold the views out of his office in Washington because they featured visitors and not Mount Vernon. In this way, Dillon was making money on the side. The MVLA ultimately resorted to sending an official reprimand to Dillon for his zealous behavior.

Having heard various complaints from the visitors, the Vice-Regent for Massachusetts moves that Mr. Dillon the photographer be ordered to refrain from importuning the public in regard to having their photographs taken. And also giving information about the Mansion. That he should give his attention to his legitimate business of selling views of Mount Vernon, and only take groups when requested, as by doing otherwise he is not keeping within his contract.

A year after this letter was issued to Dillon, the MVLA observed that Dillon had complied fully with this request.

Luke Dillon conducted his business until the end of his contract with few additional incidents of "importuning" visitors. When his contract did expire, the MVLA decided that with regard to making exclusive contracts with photographers "it is at present inexpedient to restrict this right." In 1894, the MVLA again declined to enter an agreement with any other photographer.

Amateur Photography

The demise of the "official photographer" at Mount Vernon occurred for several reasons.

First, photography was becoming increasingly popular. When Alexander Gardner began taking pictures at Mount Vernon, few people could afford the necessary equipment. However, by the end of the nineteenth century, photography had become accessible to the amateur. In 1895, the first year that amateur photography was not restricted, Mount Vernon Superintendent Harrison Dodge noted that "the privileges thus granted were apparently very much enjoyed and never abused."

Secondly, the MVLA's inability to recover the negatives of Alex Gardner and N.G. Johnson plagued the Association for thirty years. Mount Vernon could not prohibit the sale of views in Washington by companies that acquired the negatives. In the case of Johnson, a primitive black market allowed the MVLA to be exploited. The increased supply of views meant that Mount Vernon no longer had a monopoly on its own photographs.

Finally, the MVLA had a history of being duped by profit-minded photographers. For three decades, a portion of the MVLA's revenue was lost to its photographers as a result of loose contract agreements and soft management. Not until the era of the exclusive contract had ended did the MVLA show significant profits from selling photographs of George Washington's home. In this respect, the MVLA was also troubled in its contract dealings with boat companies that brought visitors to Mount Vernon before the construction of a railroad.

Despite these incidents, some of the work of these three photographers has survived to form an excellent study collection at Mount Vernon. Currently, there are over 4,500 photographs showing all aspects of Mount Vernon that document the estate's late nineteenth-century history. Photographs showing George Washington's home that are discovered in attics or old trunks are frequently presented to Mount Vernon by their owner, and thus become a part of the permanent record of this historic home.