The cherry tree myth is one of the oldest and best-known legends about George Washington. In the original story, when Washington was six years old, he received a hatchet as a gift and damaged his father’s cherry tree with it. When his father discovered what George had done, he became angry. Young George bravely said, “I cannot tell a lie…I did cut it with my hatchet.” Washington’s father embraced him and declared that his son’s honesty was worth more than a thousand trees.1

Origin

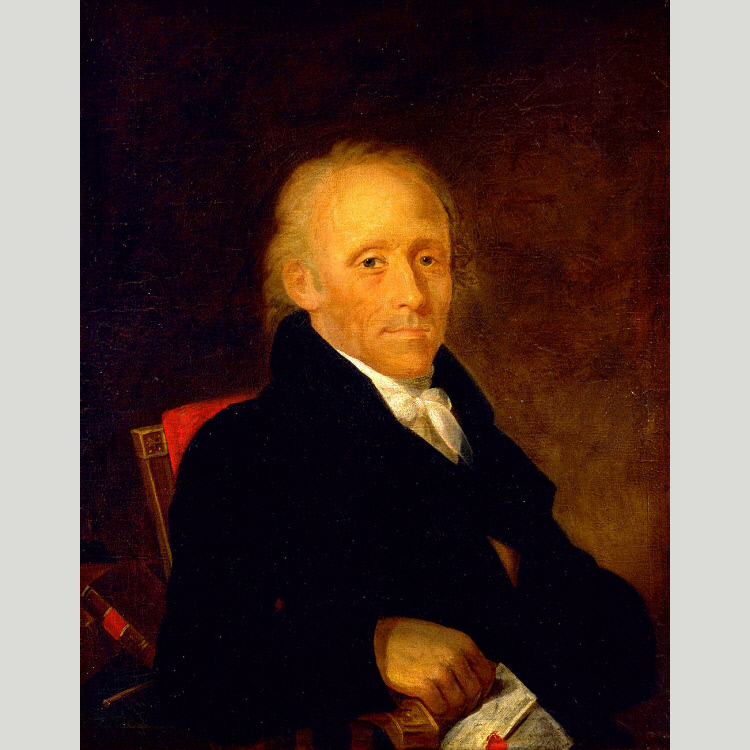

This iconic story about the value of honesty was invented by one of Washington’s first biographers, a traveling minister and bookseller named Mason Locke Weems. After Washington’s death in 1799, people were anxious to learn about the first President. Weems explained to a publisher in January 1800:

"Washington you know is gone! Millions are gaping to read something about him...My plan! I give his history, sufficiently minute…I then go on to show that his unparalleled rise and elevation were due to his Great Virtues."2

Weems's biography, The Life of Washington, was first published in 1800. It became an instant bestseller due to its approachable style. However, the cherry tree myth did not appear until the book's fifth edition in 1806.

Weems had several motives when he wrote The Life of Washington. Money was certainly one of them. He rightly guessed that if he wrote a popular history book about Washington it would sell.

A Federalist admirer of order and self-discipline, Weems also wanted to present Washington as the perfect role model, especially for young Americans. The cherry tree myth and other stories told readers that Washington's public greatness was due to his private virtues. Washington's achievements as a General and President were familiar to people in the early nineteenth century, but little was known about his relationship with his father, who died when Washington was only eleven years old.3 There is almost no surviving historical evidence about Washington's relationship with his father, and Weems’ claims have never been verified.4

As a result of his success, Weems is now considered one of the fathers of popular history. Even Abraham Lincoln recalled reading the book as a child.5

Development in the Nineteenth Century

In the 1830s, William Holmes McGuffey turned Weems' tale into a children's story to be included in his textbooks. McGuffey was a Presbyterian minister and a college professor who wrote about teaching morals and religion to children. First published in 1836, McGuffey's Readers remained in print for nearly a hundred years and sold over 120 million copies. It taught the myth of the cherry tree to millions of American students.

McGuffey's version of the cherry tree myth appeared in his The Eclectic Second Reader for almost twenty years. McGuffey made Washington's language more formal, and he showed more respect to his father's authority. For example, when Washington's father explains the sin of lying, Weems says Washington spoke “very seriously while McGuffey has young George respond tearfully.6 Follow-up questions at the end of McGuffey’s cherry tree story reinforce its message: “How did his father feel toward him when he made his confession? What may we expect by confessing our faults?"7

The Cherry Tree myth also appeared outside of books, as the case of Joice Heth shows. Joice Heth was an elderly enslaved woman purchased by P.T. Barnum in 1835. He made her into a sideshow attraction, billing her as an enslaved woman who had raised George Washington. (If true, this would have made her 161 years old.) The stories she told about Washington, including the cherry tree myth, were right out of Weems’ writing. Many people saw Heth as credible because she was telling stories that people already knew.8

Legacy

The cherry tree myth has endured for more than two hundred years. It remains influential in Americans' beliefs about Washington. It has been referenced in countless books, movies, and television shows. The story has been featured in comic strips and cartoons, especially in political cartoons.

Author: Jay Richardson, George Mason University Last Updated by: Charles Greco, October 4, 2023

Notes

1. Mason Locke Weems, The Life of Washington the Great (Augusta, GA: George P. Randolph, 1806), 8-9.

2. "Mason Locke Weems to Mathew Carey, January 12, 1800," in Paul Leicester Ford, Mason Locke Weems: His Works, His Ways: A Bibliography Left Unfinished, 3 vols. (New York: Plimpton Press, 1929), 2: 8-9.

3. Proposals of Mason L. Weems, Dumfries, for publishing by subscription, The Life of George Washington, with curious anecdotes, equally honourable to himself and exemplary to his young countrymen (Philadelphia: Carey, 1809).

4. Edward G. Lengel, Inventing George Washington: America's Founder, in Myth and Memory (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), 23.

5. Abraham Lincoln, “Address to the New Jersey State Senate,” Collected Works, 4:235–6.

6. Mason L. Weems, The Life of Washington the Great: Enriched with a Number of Very Curious Anecdotes, Perfectly in Character, and Equally Honorable to Himself, and Exemplary to his Young Countrymen, (Augusta, GA: George P. Randolph, 1806), 13; William Holmes McGuffey, The Eclectic Second Reader (Cincinnati: Truman and Smith, 1836), 113-115.

7. Ibid 113-115.

8. Lengel, Inventing George Washington, 30; Reiss, Showman and the Slave, 62-63.

Bibliography

Harris, Christopher. "Mason Locke Weems’s Life of Washington: The Making of a Bestseller." Southern Literary Journal, 19 (1987), 92-102.

Lengel, Edward G. Inventing George Washington: America’s Founder in Myth and Memory. New York: HarperCollins, 2010.

McGuffey, William H. The Eclectic Second Reader. Cincinnati: Truman and Smith, 1836.

Weems, Mason L. The Life of Washington the Great: Enriched with a Number of Very Curious Anecdotes, Perfectly in Character, and Equally Honorable to Himself, and Exemplary to his Young Countrymen. Augusta, GA: George P. Randolph, 1806.