General Braddock joined a contest in North America that began in 1754. Failed diplomatic efforts and an embarrassing showing by Virginia colonists at Ft. Necessity in 1754 prompted a more substantial military response by Britain. Braddock was expected to eject the French forces building Fort Duquesne in the Ohio Valley. To accomplish his mission, Braddock had been given extraordinary powers as commander of British forces in North America. The king anticipated that the colonists would unite under Braddock’s leadership in response to the French challenge to British claims in the valley, but unity never materialized.

Braddock was well qualified for command by 1755. He first joined the Coldstream Guards in 1710 and had earned a reputation as valiant officer in Britain’s siege of Bergen op Zoom in 1747. Promoted to Major General, Braddock commanded two regiments raised in 1741, the 44th and 48th Regiments of Foot. Much of their military experience consisted of parade ground close-order drills. Inexperienced regular soldiers, George Washington later described their battle performance as “dastardly behavior.1”

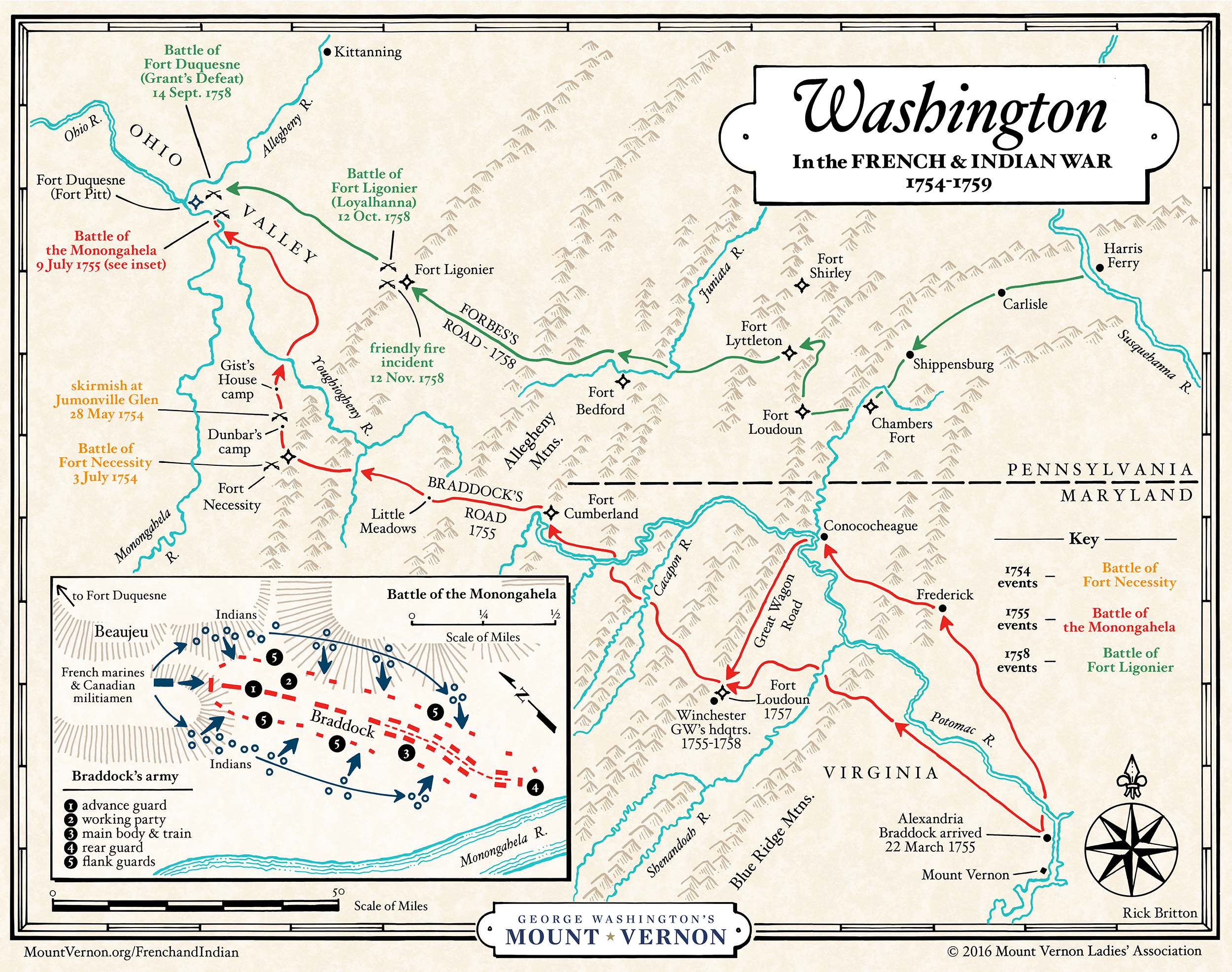

Braddock’s guards reached Virginia in February of 1755. The British aimed at conquering French forts Machault, Le Boeuf, and Presque Isle that dotted key points along the northern border. Fort Duquesne, the last domino in the series of fortifications, would be isolated for a final, glorious British victory. Braddock immediately coordinated his military efforts, instructing the governors of Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts on what each should contribute to the effort. Unaccustomed to Braddock’s forcefulness, some governors bristled at his demands, which included funds to pay his army’s expenses. Quaker dominated Pennsylvania rejected his demands for money and men, even though the conflict was on the colony’s western frontier. Braddock nonetheless prepared to launch his expedition from Will’s Creek and Ft. Cumberland in western Virginia.

Many historians argue that Braddock’s two-thousand man army was at a disadvantage without Native American allies on the expedition. On the frontier, Native allies could quickly shift the outcome of battle. British trader and frontiersman George Croghan, then deputy chief to Sir William Johnson, superintendent of northern Indian affairs, met with Braddock and key Indian leaders to cement an alliance. Yet, General Braddock is commonly accused of ignoring any and all assistance from Native Americans, even rejecting the help of Moses the Song, a Mohawk, who had a copy of Ft. Duquesne’s layout made by Captain Robert Stobo. George Washington left Stobo at the fort in 1754 to guarantee the safe return of twenty-one French prisoners. Braddock appears to have ignored what should have been valuable intelligence on the French position along the Ohio River. Whatever his reasoning, Braddock’s army had few Native allies serving in it, which some historians argue cost the lives of his soldiers.

The army progressed slowly from Ft. Cumberland, cutting a road as they moved toward the Forks of the Ohio. Carving a road for wagons and cannons was a painstakingly slow process; with each passing day the French made more progress on their fort at the juncture of the Ohio, Allegheny and, Monongahela Rivers. Resolute in his mission, Braddock formed 1,300 of his men into a flying column to advance ahead of the remaining army, which would finish cutting the road and bringing up the wagons and cannons. The column outpaced its supplies and reinforcements, both of which likely contributed to the disastrous consequences on 9 July 1755. Braddock’s men advanced until they were a little less than ten miles from Ft. Duquesne; they made it no closer.

The army progressed slowly from Ft. Cumberland, cutting a road as they moved toward the Forks of the Ohio. Carving a road for wagons and cannons was a painstakingly slow process; with each passing day the French made more progress on their fort at the juncture of the Ohio, Allegheny and, Monongahela Rivers. Resolute in his mission, Braddock formed 1,300 of his men into a flying column to advance ahead of the remaining army, which would finish cutting the road and bringing up the wagons and cannons. The column outpaced its supplies and reinforcements, both of which likely contributed to the disastrous consequences on 9 July 1755. Braddock’s men advanced until they were a little less than ten miles from Ft. Duquesne; they made it no closer.

The outcome of the Battle of Monongahela astounded George Washington, then serving as one of Braddock’s aides-de-camp. Washington believed Braddock’s force easily outnumbered the advancing French enemy, which delivered a devastatingly lethal attack. The French force was bigger than Washington knew, but he was right in that Braddock’s army was larger. Washington did not misinterpret the assault on the British force, which lasted but a few hours. French attackers killed or wounded more than half of Braddock’s men and decimated his officer corps. Sixty of the eighty-six officers were dead or wounded by the third hour of battle. Remarkably, George Washington escaped with only several near misses; he informed his mother that there were four bullet holes in his uniform and that two horses had been shot from underneath him. The often cited July 18, 1755 letter to his mother Mary included only one statement about General Braddock: “The General was wounded, of which he died three days after.2”

General Braddock fought tenaciously, having four or perhaps five horses shot out from under him before himself being wounded in the arm and abdomen. In disarray, Braddock’s army retreated from the battle, their wounded general in the back of a wagon. The French victory over Braddock at the Battle of the Monongahela kept the Ohio Valley firmly in French hands for three more years and cemented the legacy of the general in American history as an example of British failure.

Learn more about the sash Edward Braddock gave George Washington at the Battle of the Monongahela and the efforts to replicate it.

Eugene Van Sickle, Ph.D. University of North Georgia

Notes:

1. George Washington to Mary Ball Washington, 18 July 1755, Founders Online, National Archives, accessed April 11, 2019, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-01-02-0167.

Further Reading:

Anderson, Fred. 2006. The War That Made America A Short History of the French and Indian War. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Cassell, Frank A. 2005. “The Braddock Expedition of 1755: Catastrophe in the Wilderness.” Pennsylvania Legacies 5 (1). The Historical Society of Pennsylvania: 11–15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27764968.

Cohen, Eliot A. 2011. Conquered into Liberty Two Centuries of Battles Along the Great Warpath That Made the American Way of War. New York: Free Press.

Hinderaker, Eric. 1997. Elusive Empires Constructing Colonialism in the Ohio Valley, 1673-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keegan, John. 1997. Fields of Battle The Wars for North America. New York: Vintage Books.

Preston, David L. 2007. “"Make Indians of our White Men": British Soldiers and Indian Warriors from Braddock's to Forbes's Campaigns, 1755-1758”. Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 74 (3). Penn State University Press: 280–306. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27778783.

Weidensaul, Scott. 2012. The First Frontier The Forgotten History of Struggle, Savagery, and Endurance in Early America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.